Breaking the negative scale cycle of Jewish institutions

How resource centralization and a renewed focus on demand generation could address the challenges of subscale Jewish institutions

Welcome to The Business of Jewish, an insider/outsider's perspective on the management of professional Jewish organizations. Please find over 18 previously written articles here. If you’d like to sign up to receive a free monthly email, you can do so here.

This Substack often explores the fundamental business model challenges facing many Jewish organizations today. As a result of these challenges, many Jewish organizations grapple with revenue shortfalls, sluggish philanthropy, and a waning sense of forward momentum in advancing their missions. At the heart of these issues often lies a core problem: Insufficient demand.

Demand, at its core, reflects how effectively Jewish organizations meet the evolving desires of their communities. Some Jewish communal sectors struggle to keep up with these shifting expectations—a difficult task, especially as for-profit entities pour resources into capturing consumer attention. As discussed in a previous piece, “Winning the Competition for Time,” experiences as diverse as coffee shops, social media, playgrounds, and other immersive experiences fiercely compete for individuals' limited time and attention. Meanwhile, Jewish institutions that compete in the battle for mindshare often find themselves outpaced, without comparable resources to draw upon.

One response to this demand challenge has been the Jewish community’s creation of new, niche institutions that speak to highly specific audiences. In the past 20 years, we’ve seen a proliferation of minyanim that appeal to a range of political and religious preferences. Day school choice, too, has expanded since the 90s and 00s, with new schools that resonate with particular sub-demographics. The outcome of this proliferation has been meaningful and impactful for the subsegments served—yet the model also highlights an inherent limitation.

With both a shrinking demand base and an increasingly segmented community, many of these organizations deliver real value but operate at what can be described as subscale.

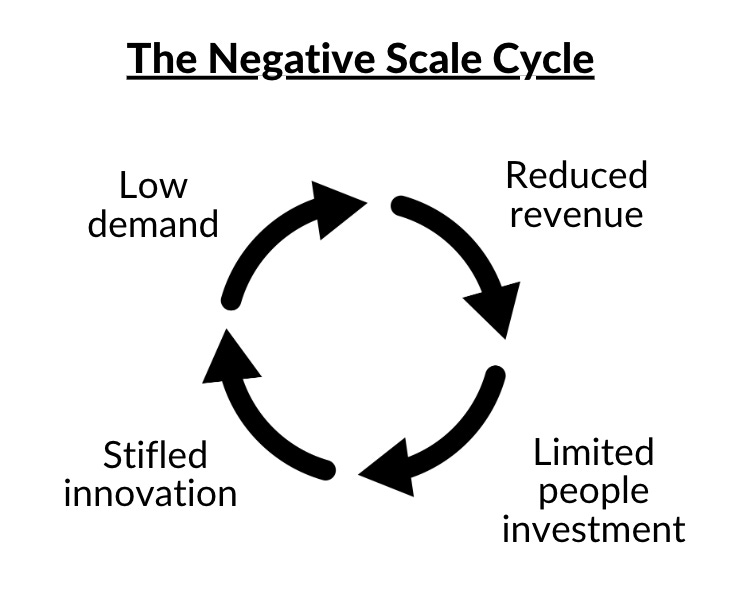

When an institution operates below optimal scale, its financial health and sustainability suffer. Limited revenue restricts the ability to reinvest in critical areas, especially the human resources essential for innovation and growth. As funds become increasingly scarce, organizations often stretch administrative and leadership roles—the very positions needed to drive forward-thinking programs and services. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle: Low demand leads to reduced surpluses, which forces cuts in essential investments in people, making it even harder for these organizations to innovate.

In turn, the leaders of these organizations find themselves stretched thin, pulled in countless directions and without the necessary bandwidth to dedicate time to strategic evolution. These leaders are caught between fulfilling their increasing day to day responsibilities and trying to secure future growth—a tension that inhibits their ability to actively respond to changing demands.

Breaking the negative scale cycle

Breaking this cycle isn’t easy. The faster it spins, the harder it becomes to build positive momentum. It’s up to Jewish leaders and their boards to recognize the cycle and move beyond incremental strategies.

Idea 1: Pursue strategic centralization

One way to break the cycle is through strategic centralization. Across many Jewish communities, clusters of similar organizations—synagogues, day schools, Hillels, camps, and social service agencies—operate independently, often within close proximity. Here in Boston, for example, we have over 100 synagogues, a dozen overnight camps, and 14 day schools.

While each of these institutions rightly pursues its unique mission and identity, they often hire similar roles. A day school might employ a CFO, accountant, head of development, head of facilities, head of communications, and many other overhead roles. Another school 10 miles away might be smaller and not have all of those specific roles, but nonetheless operate with many of them.

This pattern leads organizations to compete for both limited financial resources and a shrinking talent pool, resulting in significant variation in the expertise and effectiveness of those in key roles. The outcome is often a cycle of duplication and missed opportunities, where leaders of smaller organizations are stretched thin, managing administrative tasks that, while important, are not uniquely critical to fulfilling their mission.

There’s an opportunity for central organizations, like Federations or large foundations, to take a proactive role in shaping Jewish ecosystems through coordinated support. By facilitating partnership discussions among organizations that share common needs, these central entities could help reduce redundancies and free up leaders’ time to focus on what they do best. This is hard work and requires concerted investment in a process that harbors trust and a vision for the future. Centralization while maintaining unique identity carries precedent in non-Jewish spaces, but has seen limited traction in Jewish circles.

The most cited benefits of centralization are typically cost savings, but the potential gains in talent and time may be even more impactful. While cost reductions have a natural limit, the opportunity for leaders to reclaim their time—allowing them to focus on advancing their organization's mission—has no such cap.

Idea 2: Prioritizing demand generation

A perhaps simpler approach than centralization is to re-prioritize activities that drive demand and, in turn, revenue. While generating demand can be challenging for Jewish institutions, it serves as a powerful financial lever. Jewish camps, synagogues, and day schools, for example, often retain their constituent base for several years. For a day school with a net tuition of $15,000, attracting a single Kindergarten student and maintaining low attrition can create a nine-year recurring revenue stream of over $100,000. Similarly, overnight camps, with their high retention rates, can turn $10,000 in annual tuition into a multi-year annuity with low variable costs. If such revenue streams were translated into endowment campaigns, they would require raising millions of dollars.

In some organizations, admissions or membership functions are viewed as passive, with an expectation to respond to demand as it arises, rather than actively developing a strategic marketing and “sales” plan. In others, there is a baseline set of activities considered necessary for sales and marketing efforts, but they often fall short of the proactive approach needed to drive growth.

What would it look like for organizational leaders, including CEOs/Rabbis/Exec Directors, to focus more of their time on driving demand? Typically, the leader of an organization is its most effective salesperson, but they are often stretched thin, managing the many facets of running the institution. While there is no clear answer for the ideal time allocation, the economics of prioritizing demand generation are compelling. By dedicating more resources to this area and formalizing a plan for human and financial capital, organizations could experience a multiplicative effect, scaling their impact and sustainability.

Conclusion

Increasing demand is one of the more challenging levers for Jewish organizations to pull. It's often easier to look at an income statement and make cuts or approach donors for increased support. However, shifting the mindset of constituents—convincing them to invest their time and money—requires a deeper, more thoughtful approach. When demand is reduced, it can create a cycle where leadership teams, already stretched thin, struggle to focus on breaking out of it.

Perhaps it's time to reflect on whether our organizations have the capacity to navigate the broader shifts in how consumers allocate their time and attention. While incremental tactics may still occasionally work, they might not be enough in sectors where demand is particularly weak. Could there be room for bolder action—maybe even a more fundamental rethinking of how we approach growth and sustainability?

________

The Business of Jewish is a free bi-weekly newsletter written by Boston based consultant Ari Sussman.