Deriving productive insight from Jewish organizational benchmarking

Tangible suggestions to build trust and insight in the benchmarking process

Welcome to The Business of Jewish, an insider/outsider's perspective on the management of professional Jewish organizations. If you’d like to sign up to receive a bi-weekly email, you can do so here.

The purpose of benchmarking is to garner insight from comparing aspects of your performance to other relevant organizations. The theory goes that if you can define a “standard” you can see how your organization stacks up against it and plan out a path for betterment, whether that means cutting costs, boosting efficiency and productivity, or growing revenue. While benchmarking doesn’t tell you how to improve performance it can shine a light on an area worth investigating.

In the business world benchmarking is commonly used by investors and operators. Investors use benchmarks to help gauge current and predict future performance and see how each of them will impact company valuations. Operators use benchmarking as a smoke signal for how to invest their own time in diagnosing performance improvements. For example, a discount retailer might look at their gross margin % (revenue less product costs) and compare themselves to other discount retailers to gauge relative performance. If they find they are subpar they might start asking why and going category by category to assess profitability.

The same philosophies behind benchmarking that apply to corporate organizations could apply to Jewish communal organizations. Unfortunately, more commonly than not, my experience thus far has been that some Jewish organizations don’t benchmark at all while others have been challenged to use benchmarks productively.

Reasons for lackluster benchmarking among Jewish organizations

There are a variety of reasons benchmarking is challenging for Jewish organizations. Some of these certainly apply to benchmarking outside of business in general (not just Jewish orgs).

Common definitions can be hard to define

There are certain measures of performance in the business world that are either widely accepted or that sometimes have standard definitions. Benchmarks like gross margin, cost of customer acquisition, or net income are measured in a standard enough way. They are each reflections of the fundamental health of a business and generally have common accounting definitions which helps unify how they are measured.

Further, specific industries have come up with their own shareable measures. In the online business world companies benchmark on things like cost of customer acquisition, conversion rate, average order value, and repeat rate. Because analysts use these measures to publicly assess company performance and people contrast these measures as they move from company to company professionals derive a perspective on what “good” looks like across certain dimensions. That said, even in the business world these measures can be very deceptive. Questions come up like “Does average order value include shipping revenue?” or “Over what time period is conversion rate measured?” Each of these questions create important nuance that throws into doubt the validity of the measure. A flawed definition effectively makes a comparison useless.

In the Jewish world, at best simple financial measures like revenue and operating profit can be shared and have common accounting definitions. These measures can orient an investor as to the organization’s size but don’t really yield insight. A level below key financial measures are things like school enrollment, campers per session, or JCC members. These are likely the best, most straightforward measures we have and are easy to understand measures of progress.

Once we get past very basic participant data the definitions become much harder to nail down. If camps wanted to benchmark campers per staff person it would need to be carefully defined to only include bunk counselors and not include unit heads or CITs. As an example in a different space, if day schools wanted to benchmark on the size of their enrollment funnel the schools would need to come up with a common definition for what it means to be in the funnel - Does collecting an email address count? Do they have to come to an event at the school to count? It’s hard enough for school’s to collect data on an annual basis that matches last year’s definition, let alone coordinate across schools to find a common definition.

The challenge of coming up with useful questions

Another easy place to fall down when benchmarking is assessing what will actually be interesting. The consumers of this information are typically either a federation/foundation (i.e. investor or ecosystem shaper), organization operators, and lay leaders.

Perhaps the hardest task when benchmarking is to make a judgment as to what end product will drive the greatest amount of insight. As if that isn’t hard enough you then need to figure out how to most simply ask the question in a way that sufficiently defines the variable in question.

If you fail at any of these steps the data can be rendered completely useless by any of the constituents, which is a collective waste of time, and further erodes constituent trust.

Creating actionable insight is hard

There can be a tendency when engaging in data collection to invest a bunch of time getting the survey out the door and then to underinvest in the analysis post collection. This is a natural reaction to a process where there are countless hours devoted to building out hypotheses, figuring out the key questions, designing the survey, framing it to participants, and then making sure the participants answer.

Perhaps the most important part of this investment in benchmarking is grappling with what you’re getting back and figuring out how to frame it to the appropriate audience in a way that resonates. Actionable insight is where the rubber meets the road on benchmarking and doing it well requires thought and time. Explaining to a camp that their tuition assistance as a % of collected revenue is high is fine, but if you can’t convince the operating camp that the peer group you are benchmarking them against is the right one and pair it with credible insight, the question probably wasn’t worth asking in the first place.

Unnecessary collection erodes trust over time

Typically it is the role of a Federation or perhaps a Foundation to collect and analyze data for the purposes of benchmarking. Unfortunately for all of the reasons described here creating value out of collected benchmarking data is very hard. As a result, it can be easy for a Federation or Foundation to garner a reputation for unnecessary data collection. Once this reputation is gained it can be hard to shake and effectively can become part of the ‘brand’ of that data collector. Thus, even if a single individual is using all of the right strategies and tactics, the cooperation they get from partner institutions might be colored by years of varied execution on other forms of benchmarking.

Shortage of institution time to diagnose problems and take action

The last step is finding a willing partner on the institution side to take the insights and do something with them. Imagine you are benchmarking for a camp and tell them their food cost per camper has grown at a higher rate than their peers over the past 3 years. Let’s also say you have convinced them that the cohort group you’re comparing them against is relevant. From there that organization needs to take that data seriously enough to grapple with it. In this example case the organization might do one of the following:

Look at what specific subcategories of cost have driven those increases.

Compare those subcategories to measures of inflation over the same time period to see if you’re experiencing something normal.

Talk to your peers to see how they are grappling with food cost increases and whether your tactics are distinct from theirs.

It takes a certain amount of energy and skill set to ask questions like this and analyze past performance. In order for this data to be used productively you need willing and capable institutional partners.

Suggestions on how to improve benchmarking

Given all of the difficulties described above the question becomes what principles or ideas we can use to make it more probable that we can derive value from benchmarking.

Here are a few tangible ideas.

National orgs invest in space-specific collection

National umbrella organizations are in the best place to build or partner with credible data collection sources. Prizmah, the national day school association, has built and invested in a productive relationship with the national association of independent schools (”NAIS”) who has painstakingly built their own national data collection device called “DASL” over 20+ years. This system has not only been optimized to define school-specific terms in common ways, but it has an easy to understand user interface for data collection, and do-it-yourself charting tools for analysis.

DASL has done the hard work to define terms in a way that minimizes ambiguity and talks the language of school operators. As just one example, they grappled with the complexities behind topics like ‘school attrition’ and differentiate between students who are dismissed or left vs those who voluntarily elected not to return vs those who were perhaps exchange students and were by design only in the school for a year. Understanding the nuance behind these definitions requires insider knowledge that is best defined centrally. In this specific example, there is an objectively right answer in how you call out the line items of attrition that only need to be solved once.

While DASL works well as a data collection device for private K-12 schools, I don’t know of a common data collection device for early childhood programs. Here in Boston, when we went to study our own early childhood programs we needed to navigate definitions on our own. We used a standard survey collection device, which allowed for easy data entry, but had limited mechanisms to clearly define terms, and certainly didn’t have self serve analysis tools. It will take years of local refinement and investment to get this right, not to mention countless hours of wasted time by local organizations answering questions that aren’t defined accurately enough. Worst of all, there are likely many other Federations/Foundations struggling with the same process in analyzing their early childhood partners.

These are all good reasons to have a national partner with experience who has spent the time defining common terms and who is committed to consistent improvement year after year. These organizations may not exist in every single industry, but national umbrella orgs should attempt to forge these partnerships. If no secular partner exists there is merit in figuring out what custom solutions look like that can be deployed across regions.

Design surveys with the end in mind

Ultimately, the purpose of asking institutions to enter data is to be able to tell a story that sheds actionable insight. As such, good questions are derived when you think back from the end insight you want to deliver. For example, when comparing early childhood centers to another a hypothesis might be that center directors are overburdened with clerical tasks. This might lead to a set of questions that attempt to ask center directors for a breakdown of their time into relevant categories (i.e. in classroom teaching, in classroom supervising, finance activities, etc). This is, however, not where to stop. The additional two questions to ask in this case are:

Can I get a reliable estimate from directors on time usage? Will they have a good enough sense to answer this question in a way that allows for valid comparison?

If I collected the perfect data set and presented this information to directors, would they do something about it?”

If the answer to either of these questions is “No” it probably does not make sense to ask this question. In this case, if I were a center director and told I spent more time in class teaching than my peers, I might doubt the benchmark set. For example, If I run a small center with minimal staff, maybe it’s appropriate for me to spend more time actually teaching? If I run an independent center and don’t have a choice but to do some finance work on my own, maybe it’s fine that I spend some time in that category.

Unfortunately designing with the end in mind is hard and is impossible to get right. Even those experienced in this work will get this wrong. In my experience, the only way around this is to make a best effort and be committed to refining the questions you decide to ask for the next year.

Explain the transparent “why” of data entry

The way to combat institutional partner skepticism on data entry is to hammer home the “why” behind data entry. When we engaged in data entry for Boston area day schools we did our best to tell schools that this year’s process would be imperfect. We explained the various hypotheses that we had in various areas of school operations and told school leaders how we believed they could use the data. We also pledged that we would do our best to create insight out of the data we were collecting and then scrap the questions that did not lead to actionable insight.

Last year we asked for over 300 data points. To illustrate how hard it is to get data collection right, this year we will ask for less than 100. I suspect next year we might even ask for fewer pieces of data. It felt important to take our partner organizations on this journey with us and reinforce that we were on a quest to use their time more effectively this year than last year.

Leverage audited financials to minimize partner data entry

There are typically two types of data points to be collected, financial and operational. For a summer camp operational data points might include # of campers served, # of annual campaign donors, waitlist size, or countless others. Financial data points include things like gross tuition, net tuition, food costs, security costs, etc. Operational data points require common definitions that can be hard to put a finger on. Common financial definitions can be a bit easier to come by. Fortunately, at least in the US, most camps above a certain size will conduct an external audit and thus possess a neatly defined set of financial measures.

While the definition of certain budget line items might not be identical from camp to camp, it can be a good place to start. A central data collector can pull line items like insurance costs, collected tuition, and financial aid offered directly off of a camp P&L. It’s still important to scrutinize each of these line items and ask how they might not be accurate from organization to organization. For instance, most school financials break out administrative headcount from program (teaching) headcount, but the way each institution defines ‘administrative headcount’ could be different. How do you treat the head of Judaic studies who only teaches 20% of their time? Are they in one category or the other or do you split their time using some percentage method? These are all risks to leaning too heavily on audited financials.

The advantage of leaning on audited financials is that it presents the opportunity to save partner organization time and also could increase the accuracy of data collection. If a Federation gained confidence in common definitions across partner financials the opportunity might exist to simply collect those financials and enter them into a system (or even a spreadsheet) independently, thus saving the partner organization a lot of time AND ensuring that the data is entered accurately.

Make insights as personal as possible

While Federation or Foundation insights might be easier to come by since the collector is often the end user, bridging the gap to partner organizations is hard. It’s likely not enough to simply put all of your charts in a powerpoint and send the data to partners. Given the amount of time partner organizations spend with the data vs the time Federations/Foundations spend, it’s worthwhile to customize the insights as much as possible. This might mean creating customized powerpoint for a specific org that calls out their data vs others. This could also mean creating a custom written report that calls out insights specific to an organization. At best individual organizations will grant the data collector a 30-60 minute conversation so the data collector can get their reaction to those insights and seek to optimize them for the following year.

Think hard about the right benchmark cohorts

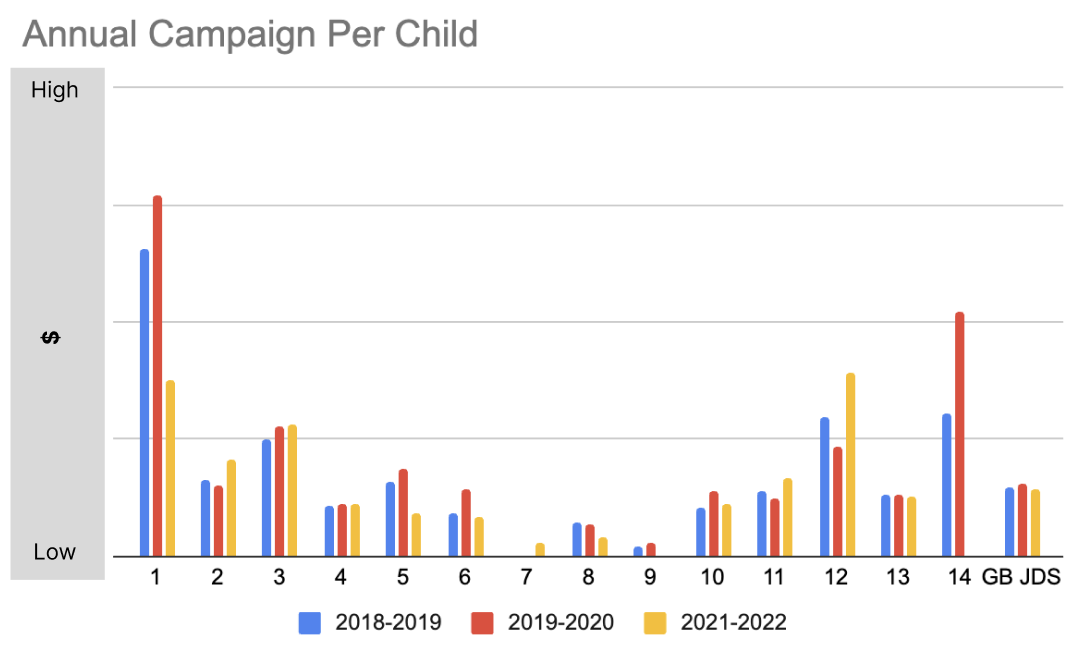

Part of personalizing the data for each organization is choosing the right benchmarks. One way I’ve seen this done effectively for day schools has been to allow each school to compare themselves to the full range of schools in their region. The chart below benchmarks annual campaign divided by total school enrollment. Each school is represented by a single number in the x-axis of the chart.

This chart serves as a barometer on how successful or not a school has been at raising annual campaign funds relative to its size. It also shows the trajectory of fundraising at one school vs another (each number represents a school).

It allows the school to answer the following questions:

How do you compare against national or regional averages? This is captured in the far right bar that shows the overall average for Greater Boston (“GB”) day schools.

How do you compare against your direct peers? This is captured in the nuance in between schools. In this case I grouped together schools with like-characteristics. This is a technique I borrowed from Toronto where Dan Held and Evan Mazin used a similar view to educate their own schools. The groupings in the chart above represent schools that serve different ages and different levels of observance. For example, schools 1-5 above are K-8 non orthodox schools and 6-8 are K-8 orthodox schools. That way, if you’re a K-8 non orthodox school you can see how you compare against your direct peers. The below view protects anonymity by using numbers (I tell each school only their number), but creates insight because it exposes the variation of outcomes in their cohort. Sometimes averages can obscure variation between schools and this view attempts to do something about that.

Lay leaders can help professionals

Interpreting benchmarks in an actionable way isn’t easy. Even with the best Federation/Foundation work and high quality interpretation, an organization needs to grapple with the insights, potentially conduct further analysis, and then integrate that analysis into their action oriented thinking. This is not a skill that every CEO has experience in. The CEO might look around their organization to figure out where the skill exists to leverage data like this. Often that person may be a lay leader. Since benchmarking is commonly used in the for-profit and/or lay leaders may possess an analytical skill set the professionals have less experience in, it’s worth seeing how individuals on your board can help with the interpretation of benchmarking.

Conclusion

Effective benchmarking can be hard enough that it’s worth asking whether it’s worth it at all. As a data collector if you don’t feel equipped to grapple with its challenges, it might actually serve as a detriment to partner organizations in your ecosystem. The purpose of this article is to surface the challenges of benchmarking and highlight the value in deliberately seeking out improvement every time you do it. Given how much time we collectively spending deriving data requests, how much time our organizations spend filling out data requests, and how much time we spend analyzing them, it’s worth putting our heads together to figure out how we can make them more collectively better.

If you are a data collector or a person whose organization submits data feel free to add suggestions that you’ve experimented with as a comment.

_______

The Business of Jewish is a free bi-weekly newsletter written by Boston based consultant Ari Sussman. Read his other articles here: